New top story from Time: “Benghazi Definitely Crossed Everyone’s Mind”: The Inside Story of the U.S. Embassy Attack in Baghdad

It was a balmy, overcast New Year’s Eve in Baghdad in 2019, and six Diplomatic Security agents were fending off enraged Iraqi protestors trying to surge into their compound. The Iraqis had started by throwing Molotov cocktails over the perimeter wall, in an apparent attempt to set fire to the embassy’s fuel depot. Now they were trying to force open two doors on either side of the compound’s northeastern gate.

Special agent Michael Yohey, a 43-year-old Army veteran from Fredericksburg, Va., could hear a lot of chaotic chatter over his radio about protestors trying to get in. He rushed toward the northernmost embassy gate to join a handful of security contractors who were already there, trying to beat back dozens of Iraqi protestors who had forced open doors on either side of the gate. But the worst had already happened: the embassy compound had been breached.

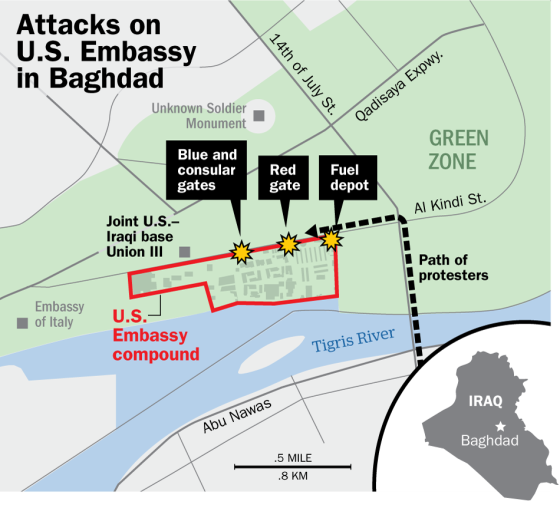

The Diplomatic Security agents entrusted with defending the sprawling 104-acre embassy complex on the western banks of the Tigris River knew Iraq’s Iranian-backed militias were spoiling for a fight. There had been demonstrations since U.S. airstrikes killed several of their members. But the Americans hadn’t heard any word of a plot against their embassy. And they had no way to know that Iraqi security forces, their host nation counterparts entrusted with keeping the outside of the embassy safe, would yield and let thousands of angry protestors pour into the international zone that housed the main U.S. diplomatic and military compounds.

It was a carefully orchestrated attack that escalated the tit-for-tat shadow war between the U.S. and Iran, with Iraq serving as a battleground and punching bag, victim and instigator. For years, Iran has been smuggling weapons across the country to arm its proxy forces in Syria and Lebanon, and the Trump Administration has looked the other way as Israeli aerial bombardments destroyed many of those shipments inside Iraq, according to senior U.S. and Iraqi officials, speaking anonymously to describe the controversial operations that Israeli officials have declined to confirm. In the last months of 2019, Iranian-backed militia groups countered by stepping up rocket and mortar attacks on U.S. diplomatic and military sites, and on Dec. 27, a barrage of those rockets killed an American contractor and injured four U.S troops. Two days later, the Trump Administration answered with U.S. strikes in Syria and inside Iraq, killing at least 25 members of an Iran-backed Iraqi militia group that was part of Iraq’s security forces and under the nominal control of the Iraqi prime minister.

The answer to that was a funeral march on New Year’s Eve for Shia militiamen killed in those U.S. airstrikes. It quickly threatened to overwhelm the U.S. embassy’s defenses, which were never designed for an onslaught by thousands of protestors without any help from the host country. In the frantic opening hours of what became a two-day standoff, the handful of Diplomatic Security agents that led the defense of the U.S. Embassy in Baghdad would think about Benghazi – the Sept. 11, 2012 militant attack disguised as a protest that overran the U.S. diplomatic facility in Benghazi, Libya, and cost the lives of Ambassador Christopher Stevens and three other Americans.

The six agents, who led the embassy’s emergency response team of roughly two dozen security contractors that day, have now been nominated for federal law enforcement awards for their bravery. For roughly ten hours, they staved off thousands of protestors that came at them in waves, lobbing flaming fuel bombs and chunks of broken concrete. No one died. None of the dozen or so Marines stationed on rooftop posts overlooking the protests opened fire. The Diplomatic Security special agents, their teams, and the U.S. military commanders in their compound just a few hundred yards away knew one wrong move could have turned the angry protest into a bloodbath, and kicked off a wider conflagration and direct combat between the U.S. and Iran.

“They were trying to get us to kill one of them,” says one of two senior security officials that took part that day, who spoke anonymously to describe the riots that threatened in the first hour to overwhelm the compound’s defenses. This account of the fraught hours at the U.S. embassy is based interviews with the six agents who were at the front lines of the protests, their award citation, and interviews with other senior U.S. officials who were part of the response.

“They’re over the bridge”

It was a Tuesday morning, and the Diplomatic Security agents knew that Iraqi militiamen had started their funeral march near the center of the capital, on a road on the other side of the wide, muddy Tigris River, across from the international zone that housed the embassy and key Iraqi government offices and residences. They were on alert, but they weren’t especially worried; they thought Iraqi security forces would keep the angry marchers from coming over the heavily guarded bridge that marks the entrance from the city center to the government area. The international zone, once called the “Green Zone,” no longer resembles the series of canyon-like high blast walls when U.S. forces occupied the country. Most of the international zone’s walls were dismantled by 2019, but there were still a few key security chokepoints where Iraqi security forces could control the public’s entry.

A bit before 10:30 that morning, Special Agent John Huey, 41, got a call from an Iraqi security official he’d befriended. They’re coming over the bridge, the Iraqi said, and there’s nothing we can do. Somewhere in the senior ranks of Iraqi government, officials had decided to allow the marchers through.

The agents, most of whom were in their command center inside the compound, watched incredulously through the security cameras that studded the exterior of the embassy compound. Hundreds, then thousands, of Iraqi protestors filled Al Kindi Street, a wide and normally empty avenue outside the embassy. “It happened very quickly from this group marching on their funeral procession parallel to the embassy. The next thing I heard is, ‘Oh, they’re on the bridge…They’re over the bridge,” recalls Huey, an Atlanta native and the incident commander for what was to unfold that day. “They were just simply allowed to drive in.”

At first, the protestors looked like they were planning a peaceful demonstration, putting up tents and political banners. They hung a massive militia flag on an apartment building across Al Kindi Street, one of several tower blocks in the government area that housed Iraqis important enough to merit a home within the semi-protected international zone.

Agent Thomas Kurtzweil, 42, had headed to the “Blue” gate as part of the agents’ choreographed security plan. The former U.S. Army infantry officer from North Carolina had seen combat in Iraq in the year after the 2003 invasion. Now he watched the protestors set up through the bulletproof windows of the gate’s small fortified reception building that embassy visitors would pass through. “I saw them bring up trucks with tents that they were offloading, and I was like, ‘Well, they’re gonna be here for a while,’” he says.

The apartment building complex, which faced the embassy, quickly became a de facto base of operations for the mix of Shia militia groups that had gathered in front of the embassy to vent their rage. It was the first of three days of mourning declared by Iraqi Prime Minister Adel Abdul Mahdi, who was furious that the Americans had killed members of the Popular Mobilization Forces that were technically under his control. That force, comprising more than a dozen mostly Shia militia groups, had been key to turning the tide against the Islamic State, which follows a violent, apocalyptic version of Sunni Islam. Roughly a third of the Shia groups were advised and supplied by Iran, which also cultivated a close relationship with the storied ISIS-fighting Iraqi militia commander Gen. Abu Mahdi al-Muhandis. After their success against ISIS, the prime minister was loath to dismantle such a popular force in a country that’s two-thirds Shia, so he brought the groups under the Iraqi security services umbrella, despite protests by Sunni and other Iraqi minority groups. Now some of those militiamen were doing Tehran’s bidding, vying for more financial support from Iran by attacking U.S. targets, according to senior U.S. administration and military officials, speaking anonymously to discuss intelligence intercepts of militia communications with the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps.

It seemed obvious to the Diplomatic Security agents that the militia members had carefully plotted out the attack. Not long after setting up their tents, they began systematically taking out the embassy’s exterior security cameras, says special agent Ian Mackenzie, 35, a former Missouri police officer. “They were going around with large poles and knocking down the cameras to limit our views on the outside of what was going on.”

The Americans inside the embassy were now on high alert, and following a set of emergency protocols they’d rehearsed multiple times. Diplomats were “ducking and covering” in safe areas away from the street.

Diplomatic Security special agent Evan Tsurumi, 41, who led the embassy’s quick reaction force that day, joined an embassy marksman on a rooftop to get an aerial view of the crowd. At that point, the crowd hadn’t yet turned violent. Tsurumi, a former New York city paramedic and Navy corpsman, saw thousands gathered outside, some carrying flags and a few carrying weapons. They were mostly young men in their early 20s, some of them wearing their forces’ uniforms. “They were very disciplined and they had an agenda,” he says, on a recent video call with TIME, together with other agents.

The crowd’s mood changed fast. A little more than an hour after they arrived, the protestors, shouting “Death to America,” gathered at the northeast end of the U.S. Embassy compound, and started lobbing Molotov cocktails – flaming bottles filled with fuel – at the embassy’s fuel depot just inside the wall. It was a strategic target that U.S. special agents say the protestors must have chosen well in advance, hoping to start a fire that would lead to a massive explosion.

Huey and special agent Mike Ross, a 37-year-old Marine reservist, ran towards the fuel farm, where the embassy’s firemen — a mixture of American and foreign contractors — were already trying to put out the blaze around the tanks before it ignited the fuel within.

“We were dodging rocks,” Huey says, “a surprisingly massive volume of rocks and Molotov cocktails.” At least they were trying to dodge them. Every agent and security force member defending the main gates that day got hit by some sort of flying projectile—chunks of brick or pavement the protestors dug out of the road outside the embassy, or baseball-sized rocks the rioters apparently brought with them from outside the international zone. The rocks mostly bounced off the American team’s military-style helmets and bulletproof vests, but were still large enough to rattle the brain, and cut and bruise arms and legs in what was to become an hours-long fight.

It wasn’t immediately clear how many attackers they were facing, or what they were trying to do. “It was very difficult to read the situation because all of us on the ground had a lot of work to do, but we couldn’t really see what was going on, on the outside,” says Ross. The agents operated on the assumption that the protestors planned to storm the compound. “We were concerned that…it could be like Iran in ‘79, basically just being massively overwhelmed by the opposition that was outside the embassy,” says Tsurumi, referring to the 1979 takeover of the U.S. Embassy in Tehran when Iranian students took 98 Americans hostage. “We had many hundreds of souls that we were responsible for, and that we probably would not be able to evacuate in time if we couldn’t hold these guys off.”

After attacking the fuel farm, the protestors moved down the embassy perimeter to their next target: the northeastern entrance, known formally as the Red gate, one of three entrances they would attack that day. The staff inside the gate’s pillbox-like security entrance had barricaded themselves inside, as their emergency protocol dictated, but the protestors were able to force open two doors on either side of the steel gate.

That’s when Yohey and his Iraqi translator rushed to the entrance in a loud-speaker-enabled vehicle that they’d use to warn protestors the rest of the day to keep away from the embassy, and radioed to all that it had been breached. Huey and Ross ran from the fuel farm blaze to join them, as did Tsurumi. “They’d also set fire to several generators, and they were still rolling the gas bombs over the wall,” Tsurumi says. “And they were flooding through the gate.”

“Everyone calm the f-ck down!”

The handful of agents and their embassy security force — roughly a dozen in all — formed a half-moon around the protestors who’d made it inside, and tried to push them out. They opened fire with a range of “non-lethal” weapons: tear gas; “flash-bang” percussive grenades; and “stinger balls,” dense rubber balls fired from grenade launchers, usually aimed at the ground to bounce up and smack the protestors in the knees or gut.

They managed to force the first wave back out into the street, but a second surge of about 50 protestors soon forced their way in. Huey was concerned his team was about to be overrun — and if that happened, he worried that the security team on the embassy buildings above would make the call to use lethal force, which he feared would draw fire from armed militia men he had spotted in the street, who had been careful not to approach the embassy compound. “We unleashed a really robust volley of less-than-lethal munitions on the crowd,” Huey says, but the rioters just kept coming.

That’s also when Huey spotted Iraqi counterterrorism troops making their way from the street through the surging protestors. They were trying to get the militia members out of the compound. “And at that point, it became very apparent to me that we needed to regain control” while also giving the Iraqi counterterrorism forces some space to work their way through the crowd and convince them to exit the compound.

Huey jumped between his line of agents and guards, and the Iraqi protestors, and in a hoarse voice, shouted to all of them, “Everyone calm the f-ck down!” And everyone, including the Iraqis, took a step back. It worked “surprisingly well,” he recalls with a grin. “And we all were able to kind of stop the aggressive onslaught that we had unleashed on these folks,” and the Iraqi counterterrorism troops were able to shepherd the militiamen out.

That was in the first hour of what was to become a day-long melee, with the protestors besieging the embassy gates in coordinated waves. Fifty or so protesters would surge at the gate and then fall back, replaced by 50 more, according to a senior security official who was monitoring the protest from the base across the street, speaking on condition of anonymity. The Diplomatic Security agents were eventually able to force the gates shut.

“Benghazi definitely crossed everyone’s mind”

Pushed back outside the compound walls of the Red gate, the protestors moved down to street to two other gates, the Blue and Consular entrances, destroying their reception buildings, then using a metal roof from a sun shelter outside as a ramp to climb over the wall. The embassy staff inside those small, fortified reception buildings had already cleared out sensitive documents and evacuated. At these other two gates, the protestors did not make it inside the embassy compound in the same numbers as at the Red gate, but they kept trying for hours.

“The rest of the day was kind of a standoff with various breaks where they would probe different defenses, throw more gas bombs” and thousands of baseball-sized rocks, Tsurumi says, describing the defensive mission as a marathon. “We were alone there without any assistance for approximately 10 hours, you know, just working creatively.”

The agents were now also serving as firefighters, as their contractors weren’t paid to fight fire while under attack. The rioters kept throwing Molotov cocktails over the wall where a number of embassy vehicles were parked, so Mackenzie, who had joined the fight at the Red gate, scrambled to find keys to the flaming vehicles, jump into them, and drive them away from the walls in order to put the fires out.

That violent first hour had shaken them all. “Benghazi, definitely…crossed everyone’s mind,” Mackenzie says.

What the agents couldn’t know from their vantage point in the middle of the fight on ground is that the U.S. military had teams on standby in Iraq, the Gulf, Europe and even back in the U.S. to flood the embassy, guard the interior and evacuate the diplomats if need be, say both senior security officials, speaking on condition of anonymity to describe the response.

In Washington, Senior State Department officials, including Secretary of State Mike Pompeo and Iran envoy Brian Hook, were watching the siege from multiple cameras that remained inside the embassy, as well as the military’s cameras trained on the street from the joint U.S.-Iraqi military base, Union III, catty corner from the diplomatic compound on the opposite side of Al Kindi Street.

In Virginia, Michael Evanoff, the then-head of Diplomatic Security, first got the call at his home a bit past three in the morning — around 10 a.m. Iraq time — just as the marchers were being allowed to cross the bridge and approach the embassy. He drove straight to the Diplomatic Security command center in Rosslyn, Va., where he could monitor what his agents were doing on the ground. A former Diplomatic Security agent with decades of experience in conflict zones, Evanoff had been hired in 2017 with one overriding order from the White House: No more “Benghazis.” The Trump Administration wanted no more U.S. diplomats lost because of indefensible diplomatic facilities.

Evanoff and his team had planned for years on how to avoid repeating a Benghazi-style disaster, and this would be their test. They had beefed up multiple layers of security inside the Baghdad embassy, as they had at other high-threat posts, adding a U.S. Marine Air Ground Task Force team in addition to the Marines who regularly protect embassies and the classified material inside. They drilled constantly on what to do if an embassy was overrun. “We are armed to the teeth and we could shred them,” he says. “But we were fortunate enough to see that their intent was to harass.”

Sitting thousands of miles away, Evanoff in Virginia, and Pompeo and the others watching from another monitoring center at the State Department, followed the lead of the most senior officer on the ground: Bryan Bachmann, the Diplomatic Security agent running the Baghdad embassy command center that day. It was Bachmann who decided his agents and the Americans’ emergency contractor security force was handling the onslaught at the gates just fine, and he made the crucial call to avoid bringing uniformed troops into the fight, judging that doing so might further inflame the crowd and turn it deadly, Evanoff says.

After Benghazi, embassies in conflict zones like Iraq and Afghanistan had already been better fortified, but Evanoff’s team took that further, installing multiple rings of mostly invisible security. In Baghdad, the gate reception buildings that visitors would pass through, which the protestors penetrated and torched, were designed to buy less than an hour of time for those inside to prepare the deadlier lines of defense, like the dozens of Marines armed with heavy automatic weapons positioned on the rooftops. The damage to the three gates was around $20 million, one of the senior security officials says, but that was deemed money well spent. It gave the protestors something to vent their rage on, and bought time for those inside to prepare.

There were some parts of Evanoff’s plan that didn’t work so well. Somehow, the mechanisms in at least one of the huge, multimillion-dollar gates got stuck, and the agents had to figure out how to dismantle the controls to close it. Agent Kurtzweil says a sharp knife proved the simplest option, and then the agents and their teams of security contractors scoured the compound for empty shipping containers, and set up a new inner ring at each of the torched entrances. In response, similar gates at other U.S. compounds around the world have now been fixed, one of the security officials says, and there’s a new standard operating procedure for improvising new gates if a compound gets overwhelmed. Fuel farms have also been fortified to withstand attack from the outside.

Waiting it out

By nightfall of the first day, the agents had secured the gates, and multiple Iraqi officials including the Minister of Interior and Iraqi militia commander General al-Muhandis had visited the crowd to calm them down. Iraqi officials tell TIME they worked as fast as they could to de-escalate the situation, which they insist was more symbolic than an actual danger to those inside. An aide to then-Prime Minister Abdul Mahdi said the U.S. airstrikes against militia members, carried out without alerting the prime minister, had created a level of anger within government ranks that had to be handled carefully.

Around midnight, the protestors stepped up their harassment again, shouting “Happy New Year, Amriki!” to the agents inside, before firing commercial-grade fireworks first into the air, and then directly at the Americans. “But it wasn’t a mortar or an RPG,” a rocket-propelled grenade, one of the security officials says, and launching fireworks to harass those inside the U.S. embassy and military compounds was also a regular weekend occurrence, the second security official says. So, the agents just hunkered down, and prepared to put out any fires the incendiary volleys might start.

Day two of the protests felt more like a PR exercise on the milita’s part, Huey says. Protestors milled about, listening to loud sound systems blaring patriotic militia music, while the Americans, including more than 100 extra Marines sent by the Pentagon, mostly waited it out. At one point, the Americans fired tear gas at an energetic group of protesters that had climbed atop one of the burned reception buildings, but for the most part, the battle was over. At the end of the day, the protestors, heeding demands from their own militia leaders to stop, packed up their tents and departed.

That’s when the U.S. military flooded the embassy with more defenses, under cover of darkness, in anticipation of the next round of payback, one of the senior security officials says. On Jan. 3, a U.S. drone strike killed Iran’s Gen. Qasem Soleimani and the Iraqi militia General al-Muhandis, accusing them of planning the U.S. embassy attack.

But this time, protestors weren’t allowed to reach the street outside the U.S. embassy. The Iraqi prime minister’s forces kept them out. Pompeo had warned him after the embassy breach on New Year’s Eve that the U.S. would “protect and defend its people” if the embassy was attacked again.

Throughout those two tense days, the agents were all getting frantic messages from loved ones back home, watching the violence unfold as it was filmed by local and international media, and the protestors themselves, in what was all about the ritual humiliation of the Americans inside. “My wife was just beside herself. It was absolutely terrifying for her,” Mackenzie says. When he returned to the U.S. weeks later, “she essentially told me, you’re not going back.” He hasn’t returned since, though Huey and some of the other agents have.

The six men were just named recipients of this year’s Federal Law Enforcement Officers Association National Award for Uncommon Valor, and the entire Baghdad security team has been nominated for the State Department’s heroism award for keeping their cool in the face of an opponent who was trying to goad them into violence.

They knew if things went wrong that night, it could start a war, Huey says. “We knew what was at stake here.” So, they kept their wits, and sense of humor, adds Ross, with a comment that brings grins from all the agents. “If it’s gonna go down, I’m at least going down smiling.”

No comments