New top story from Time: ‘Was This All Worth It?’ Grieving the Death of One of the Last U.S. Soldiers Killed in Afghanistan

Sergeant First Class Javier Jaguar Gutierrez is buried in Grave 104B of Section 14A at the Fort Sam Houston National Cemetery in San Antonio. The white marble headstone is shaded by a willowy oak and adorned with a miniature American flag and a fistful of red, white and blue flowers.

On Aug. 27, Sylvia and Javier Gutierrez make the 29-mile trip to their son’s grave site, just as they have done dozens of times since his death 18 months earlier. Time and again, they’ve come here carrying photographs and fresh bouquets and family gossip. They’ve also carried a burden inside, one no parent should have to bear: their son was one of the last two American soldiers to die fighting in Afghanistan.

[time-brightcove not-tgx=”true”]

Jaguar, 28, and an Army Ranger were shot and killed on Feb. 8, 2020. An Afghan service member turned his gun on them just three weeks before the U.S. signed a landmark peace deal with the Taliban. Despite the tragedy, the Gutierrez family managed to take a measure of solace in the fact that Jaguar would be one of the last soldiers to die in the nation’s longest war. The pain, they thought, would stop with them.

But now they were passing on their burden. The day before their visit to the cemetery, a suicide bomber had killed more than 170 Afghans and 13 U.S. service members at the Kabul airport. The grief Sylvia and Javier had endured over the past year and a half would now be felt by yet another group of shattered U.S. families, a new set of bereaved parents.

Becoming a Gold Star family is an honor that nobody seeks. No one can fathom the heartache endured by the mothers, fathers, wives, husbands, daughters and sons of the fallen. “There’s an emptiness,” Sylvia says. “I feel like I’ll never be whole again. This war—although it’s coming to an end—will not end for me.”

The Taliban’s sudden takeover of Afghanistan is a bitter reality for all Americans after a generation of war. But the jarring spectacle hit especially hard for veterans, active-duty service and the families of the 2,461 service members who have died in Afghanistan since 2001. Many questioned whether their sacrifices mattered. The Department of Veterans Affairs and military vet groups reported an uptick in calls to suicide hotlines as the catastrophic collapse of the Afghan government and rushed U.S. exit from the country unfolded on national television. “My son and those that have spilled blood there, or come back with missing limbs, they gave everything,” says Javier, a former Marine. “We’re better than this.”

Sylvia and Javier listen to satellite radio during the ride to the cemetery. Images of the ignominious withdrawal flip through their minds like a slide deck. The frantic airlift in Kabul. The desperate pleas of Afghans turned away at the airport gates. The bloody wreckage of a terror attack. The youthful faces of 11 men and two women who gave their lives to save complete strangers.

They find Jaguar’s grave along the cemetery’s main road, amid a sea of other headstones inscribed with the names of people who fought in conflicts many decades ago. Sylvia and Javier sit on the manicured grass and speak softly to their firstborn son. Through tears, they describe the latest news the best they can. They reveal their shared feelings of helplessness. They tell him they love him and miss him. They make sure to remind him they’re proud of his sacrifice. And then they head home.

The middle name Jaguar came from his father. A Desert Storm veteran with shoulder-length black hair and a passion for heavy metal, Javier had visions of his baby boy one day standing before sold-out arenas with a Stratocaster guitar. Jaguar didn’t share his father’s affinity for music. But he did love the name. “He was Jaguar from the start,” Sylvia says.

It was clear early on that Jaguar would follow his dad into military service. As a child, he’d watch old war movies, read military history books and play video games like Call of Duty. “He’d arrange toy soldiers around the rim of the bathtub and put on goggles,” Sylvia recalls. “I’d see him in there splashing like he was caught in a battle.”

This is how his family remembers Jaguar: childlike, eccentric, adventurous. His sisters, Janea, 35, and Jordan, 28, remember their brother as a goofball—a guy who would lick the remote control to keep them from changing the channel; a guy who once borrowed Janea’s three-day-old Mazda Tribute to go pick up a Gatorade, only to return 30 minutes later, drenched in sweat, having locked the keys in the car, which had also acquired a bunch of scratches. He had a contagious giggle, which could be triggered by almost anything. He played football, but he wasn’t crazy about it. He didn’t care much for school either, maintaining a C average, which his father believes was likely because of untreated dyslexia and attention deficit disorder.

Jaguar’s intelligence emerged, however, when he applied himself in the armed forces. He enlisted in 2009 at age 17, during his senior year of high school. Much to his father’s chagrin, he chose the Army like his great-grandfather Thomas Ortiz, who served during World War II, over Javier’s beloved Marine Corps. Jaguar found immediate success as an infantryman. After completing basic training at Fort Benning, Ga., he qualified for airborne school and got assigned to the storied 82nd Airborne Division in Fort Bragg, N.C. There he met Gabby, a daughter of Honduran immigrants, who worked as a waitress at an IHOP restaurant near base that he frequented. The two began dating and married a month later.

After a nine-month deployment to Iraq in 2010, he attended Special Forces assessment and selection in 2013 at Fort Bragg. He graduated two years later from the Q course, an excruciating training program that soldiers must pass to earn a green beret. When he passed, Jaguar didn’t want his mother to go to the ceremony or post photos to her Facebook feed. His reservedness about his accomplishments made Sylvia feel guilty about talking so openly about him, even after his death. But she knows what she’ll reply when she sees him in the afterlife. “I’m going to tell him that he should’ve done something else with his career,” she says, “something that people were less interested in knowing about.”

Jaguar was assigned to 3rd Battalion, 7th Special Forces Group at Eglin Air Force Base, Fla., as a Special Forces communications sergeant. He and Gabby settled into a three-bedroom, ranch-style home near base in the Florida panhandle. They had four children: Gabriel, Eden, Helen and Emee, who now range in age from 4 to 8. He was a doting and loving father who read the Lord of the Rings books aloud to his children each night before they went to sleep. He loved the fantasy trilogy so much, he would watch the movies before every deployment.

Seventh Group is a highly trained unit that primarily conducts missions in Latin America. Its members speak fluent Spanish and work with local forces in remote jungles to combat foreign threats. Yet each of the past three administrations has also deployed the elite group around the world, using it as an alternative to sending thousands of conventional military forces and risking the political blowback that comes with it.

In January, Jaguar’s 12-man team of Green Berets, named Operational Detachment Alpha (ODA) 7313, embarked on a new set of orders: deploy to Afghanistan’s Nangarhar province under a so-called train, advise and assist mission, accompanying Afghan forces who were supposedly in the lead. But that was just semantics. The “assist” part was difficult to distinguish from a traditional American combat mission. It certainly had the same risks, and the same consequences.

The call that forever changed the Gutierrez family’s lives came on a Saturday evening a little after 5:45 p.m. Sylvia and Javier were getting dressed to make a 6 p.m. Valentine’s Day party at their Baptist church. As usual, Javier was lagging, hastily buttoning his black shirt and tucking it into black slacks, when Sylvia’s phone lit up with a call from Gabby. When she picked up, she couldn’t understand her daughter-in-law. The words seemed jumbled. She punched the speaker button: “Me mataron mi esposo. Me mataron mi esposo. Me mataron mi esposo,” she repeated. “They killed my husband.”

From across the room, Javier heard what Gabby was saying, but it didn’t make any sense. What was she talking about? “My first thought was, ‘No, no, no, that couldn’t be true,’” Sylvia says. “Then I remembered that I had seen a report on social media earlier in the day of an insider attack. I put it out of my head because it wasn’t like Jaguar was the only soldier in Afghanistan.”

About two hours later, an Army officer appeared in their doorway. He told Sylvia and Javier that Jaguar’s Green Beret team had been ambushed by one of the Afghan troops they were helping. The military’s investigation into the attack—more than 100 pages of which was reviewed by TIME—is heavily redacted. The unit was assigned to help a meeting between Afghan officers to help clear the way for the peace accord that would be signed three weeks later. ODA 7313 and Afghan forces returned from the meeting to a small military base and requested a U.S. helicopter evacuation at 3:20 p.m. local time. The request was pushed back three times by higher command. The investigation does not explain why.

Around 6 p.m., the mixed group of U.S. and Afghan soldiers were unwinding and shedding their bulletproof vests after sunset prayers. It was then that Sergeant Mohamad Jawid, 23, fired two or three bursts from his machine gun into the resting troops, many with their backs turned. Jaguar was shot nine times. The fatal bullet tore through the back of his helmet and lodged in his brain, killing him instantly, according to the report. Army Ranger Sergeant First Class Antonio Rodriguez, 28, was also killed, and seven other U.S. soldiers, two Afghan soldiers and an Afghan interpreter were wounded. Within 47 seconds, Jawid sprayed 75 to 150 bullets into the group before he was shot and killed by security forces.

Investigators determined Jawid was “likely self-radicalized and influenced by Taliban ideology.” Their report does not connect his attack with another that occurred at the same base less than an hour later, in which U.S. soldiers reported being shot at from at least two positions, including a guard tower, when helicopters arrived. Javier found the report suspicious, believing the events must have been linked. He thought the U.S. government did not want to publicly acknowledge the attack was coordinated by the Taliban for fear of losing support for the impending peace deal. But he admits he’ll never know for sure.

Two days after Jaguar’s death, his remains arrived on a C-17 cargo jet at Dover Air Force Base in Delaware. President Donald Trump and Vice President Mike Pence had shown up unannounced to stand with the Gutierrez family in the winter darkness. As a light mist began to fall, the plane’s cargo hold yawned open. Six soldiers with white gloves emerged carrying Jaguar’s flag-draped transfer case off the back of the plane.

Overcome with grief, Gabby sprinted down the tarmac toward her husband’s casket. She was wailing, repeating his name, as she threw herself onto the C-17’s ramp. Two soldiers helped comfort her and carry her away. “The only thing that I was thinking was, I need to see my husband,” Gabby says. “I didn’t care about anything else or who else was there.”

The mortuary team at Dover prepared Jaguar for burial. They cleaned his 211-lb. body and washed his black hair. They put on his dress uniform teeming with medals and ribbons, including a Bronze Star, a Purple Heart and expert infantry and parachutist badges. His Special Forces tab was stitched to his upper left sleeve. A sergeant first class chevron was stitched to the right sleeve.

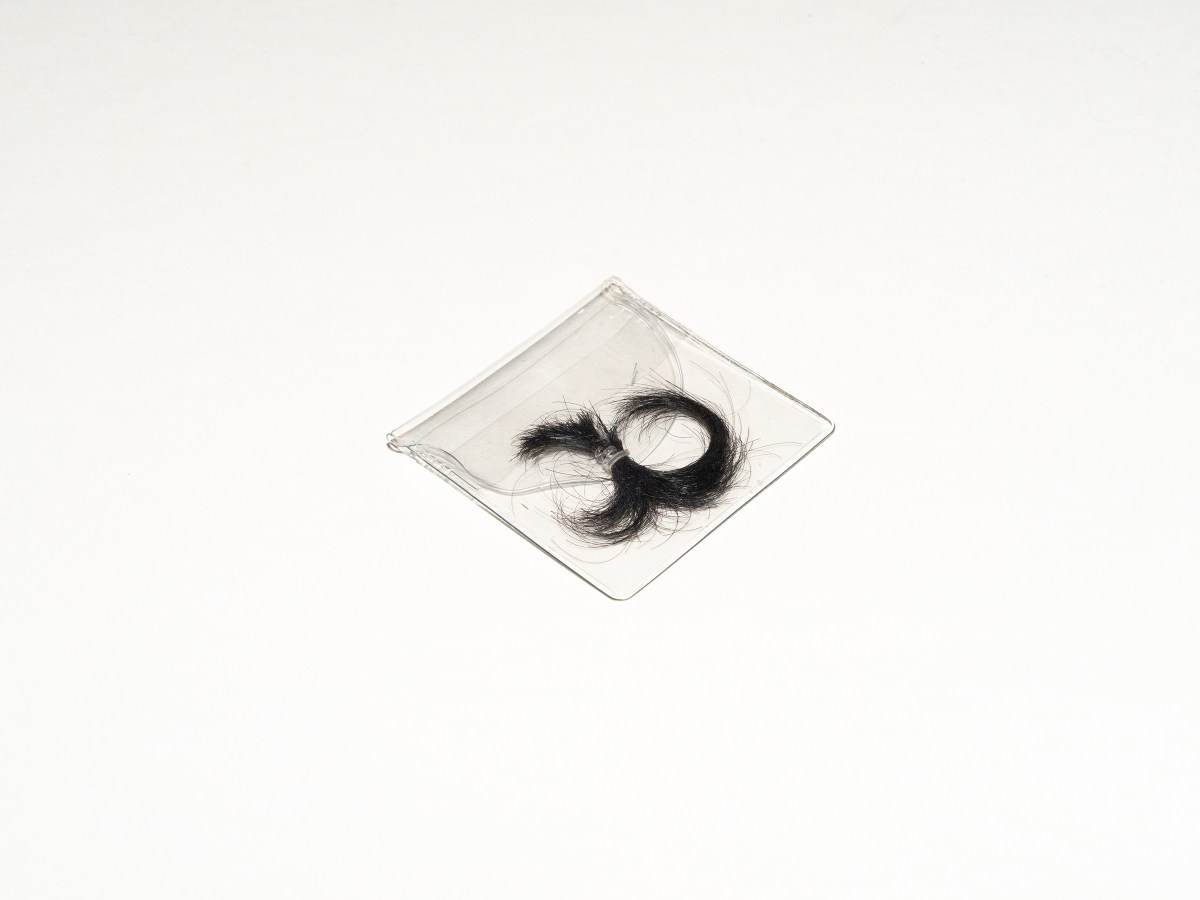

Javier chose to see his son one last time. He kissed him and touched the wounds that the morticians had labored to close. Then he looked at his boy’s face and requested a lock of his hair. “It was the only part of him that looked real to me,” Javier says.

It was raining on Feb. 20, 2020, when Jaguar returned home to San Antonio. A police cruiser and motorcycle unit led the silver hearse down the city streets. On each side of the road, hundreds of service members saluted and paid their respects to the local hero. Mourners later gathered at Community Bible Church, where his sister sang in a memorial service led by his uncle, Pastor Robert Gutierrez. “You, through all of your actions, shined a great light for Christ and for this country, and that’s something that no terrorist coward will ever extinguish,” he said.

Gabby and their four children sat in the front row. “For a long time, I’ve been on a roller coaster between being angry and sad,” she says. “The thing is: I will never see my husband grow old, and my kiddos do not have him in their everyday lives. We were denied that.”

When their son died, it felt to Sylvia and Javier as though they’d been dropped into an alien landscape. Javier compared the feeling to a vacation years ago when he and Sylvia had a stopover in Turkey. Airport officials were trying to give them directions, but they didn’t know the language. “I didn’t have the words to help myself,” he says. The family didn’t know what they should do, whom they could call or what they needed to plan for. Grief gripped them in strange places: the aisle of a grocery store, midsentence in a book. Finding moments of levity was impossible; they felt like the simple act of laughter was a betrayal.

This June, Sylvia joined a group of Gold Star mothers who meet over Zoom. She spoke with mothers who had lost their children a decade ago, and they swapped tips for dealing with the pain. It made her feel less alone, like she was finally on the right path in the recovery process. But in recent weeks, the U.S. withdrawal has called up difficult emotions. The family stayed glued to the radio, listening to the news. “The whole thing could’ve been handled better,” Javier says. “I don’t think we should stay in Afghanistan forever, but the way we’re leaving seems rushed. There’s no honor to it.”

After a war that dragged on for years, the collapse of Afghanistan happened quickly. U.S. intelligence assessments initially estimated that Afghan security forces could stave off Taliban offensives against major population centers like Kabul for a year or possibly more. In August, the timetable was sharply downgraded to 30 days or less, according to two current U.S. officials. In the end, Afghan defenses fell apart within 11 days, the troops repeatedly acquiescing to the insurgents.

President Joe Biden has yet to explain why his Administration failed to anticipate an outcome that military and intelligence officials had long predicted. Instead, Biden has remained defiant, blaming the Afghan military, Afghan leadership and the Trump Administration for the humanitarian disaster now playing out. But despite the Administration’s protests, it’s not the choice to pull out of Afghanistan that critics like Javier have seized upon. Polls show most Americans agree with the decision to pull troops out of a chronically mismanaged war. Biden ran on that policy, which was set into motion by his predecessor. It was the way in which the Biden Administration withdrew that left the families of the fallen feeling let down. “We feel betrayed,” Gabby says. “I don’t understand how the Taliban is now in power. Our soldiers deserve better.”

The Gutierrez family isn’t alone in their disappointment. Widows, veterans and military members have spoken publicly about how the pullout was being mismanaged. The widespread indignation has prompted senior commanders and leaders at the Pentagon to speak publicly about their sacrifices. “I know that these are difficult days for those who lost loved ones in Afghanistan and for those who carry the wounds of war,” Defense Secretary Lloyd Austin told reporters Aug. 18 at the Pentagon. “Let me say to their families and loved ones: Our hearts are with you.” General Mark Milley, chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, appearing alongside Austin, stated it more succinctly: “Your service mattered.”

Sylvia and Javier are convinced that it did. Jaguar’s death has become a defining element of their identity. They have transformed the sunroom at the front of their two-story brick home in San Antonio into a museum of their dead son. His hunting knives and patches are sealed away in a glass case. Books he read, awards he won, hats he wore are neatly stacked on shelves. Photos, newspaper clippings and paintings are tacked to the walls. “We just try to remember the sacrifice he made,” Javier explains. “You look at what’s happening now in Afghanistan and ask yourself, ‘Was this all worth it?’” He has to believe that it was.

No comments